Obsidian is a particularly attractive material that is utilised for the production of chipped stone tools. Not only does it have excellent technical qualities, but it is also almost magically beautiful. This is also why it is frequently classified in the category of primary valuables, the distribution of which had already achieved supra-regional dimensions during the period of the early archaic societies.

|

| The unprecedented abundance of the Carpathian obsidian sources is well illustrated by the famous depot of cores emanating from the Nyírlugos site on the Hungarian-Romanian border. According to Kasztowszky – Biró – Kis 2014. |

For the prehistoric Central European community the main source-areas for obsidian were the Carpathian basin together with the outcrops in the Zemplén hills of Slovakia and also the Tokaj-Zemplén hills in Hungary and in Transcarpathian Ukraine. In this area the local origin of the raw material was significantly substantiated. It is characterised by its appearance that has the form of small bulbs that can have a diameter of up to twenty centimetres, though frequently they are smaller than that. Even from these outcrops, however, it was possible to obtain raw material comprising high quality cores, as is evidenced at the depot of the Nyírlugos site located on the Hungarian-Romanian border and also by the long blades that are found at many Slovak prehistoric sites.

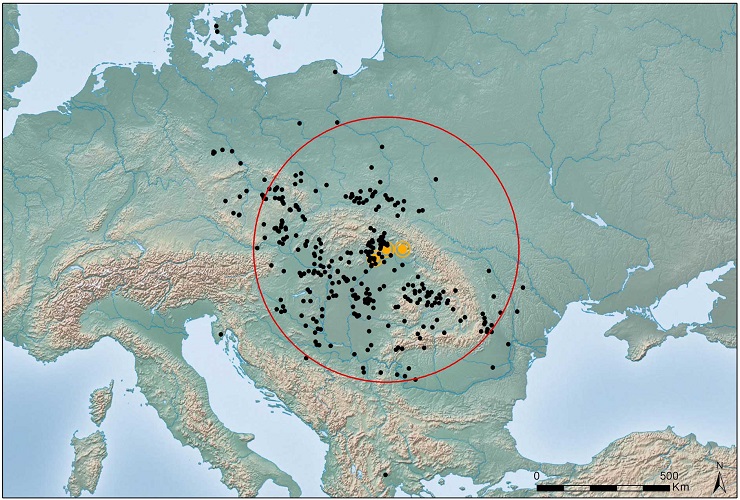

Obsidian has been in use since the Palaeolithic; the amount of its representation in the finding files is dependent on the distance from the actual source and on the competition for other high quality materials that takes place between the distribution networks. The maximum catchment area for distribution is cca. 500 kilometres from the source, as the crow flies. The Czech lands, however, already exceed this limit, as also do the findings in Istria and on the North Sea coast. Actually it is these peripheral findings that are worthy of attention. It can be assumed that the symbolic value of an artefact of this nature will increase in accordance with the distance from its source. In the more peripheral areas obsidian occurs naturally only in traces. Because its representation would not play any prominent role in regard to the community’s raw material economy, it is important to also consider the other reasons for its distribution. These, perhaps, could include its attractive appearance. On the other hand, the ease of its recognition is the reason for our sound knowledge regarding the range of occurrence of this raw material.

As is evidenced by the Czech and largely also the Moravian findings, the selection of raw materials occurred at the actual time of their distribution. The communities that inhabited the regions that were closer to the sources used more high-quality (larger) bulbs for their own needs, while the raw material of lower quality (i.e. smaller in size) was passed-on again. In the course of our prehistory we usually encountered cores and blanks with very small dimensions. This fact is indicative of what is known as the down-the-line-trade distribution scheme, while the actual number of “stops” on this journey is unknown.

|

| The total range of occurrence of Carpathian obsidian in the European prehistory period demonstrates the ease of its distribution over large distances. The source areas are indicated by the colour yellow, while the radius of the circle shown here represents a distance of 500 km from these sources. According to Burgert 2015, Fig. 2. |

Want to learn more?

- Biró, K. T. 2014. Carpathian Obsidians: State of Art. In Lithic raw material exploitation and circulation in Préhistory. A comparative perspective in diverse palaeoenvironments, eds. M. Yamada, and A. Ono, 47–69. ERAUL, vol. 138. Liège: Université de Liège

- Bloedow, E. F. 1987. Aspects of ancient trade in the mediterranean: Obsidian. Studi micenei ed egeo-anatolici 26: 59–124.

- Burgert, P. 2015. Štípaná industrie z obsidiánu v Čechách. Archeologické rozhledy 67 (2): 239–266.

- Tykot, R. H. 1998. Mediterranean Islands and Multiple Flows. The Sources and Exploitation of Sardinian Obsidian. In Archaeological Obsidian Studies. Method and Theory, ed. M. S. Shackley, 67–82. New York – London: Plenum.

- Williams-Thorpe, O., S. E. Warren, and J. G. Nandris. 1984. The distribution and provenance of archaeological obsidian in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science 11: 183–212.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.png)