|

| A view into one of the pits associated with the apparent trench in Herxheim where there is a concentration of human bones and fragments of pottery and parts of stone grinders, which have become the subject of their as yet unexplained deliberate destruction apparently during a special ritual (© GDKE, Direktion Landesarchäologie – Speyer). |

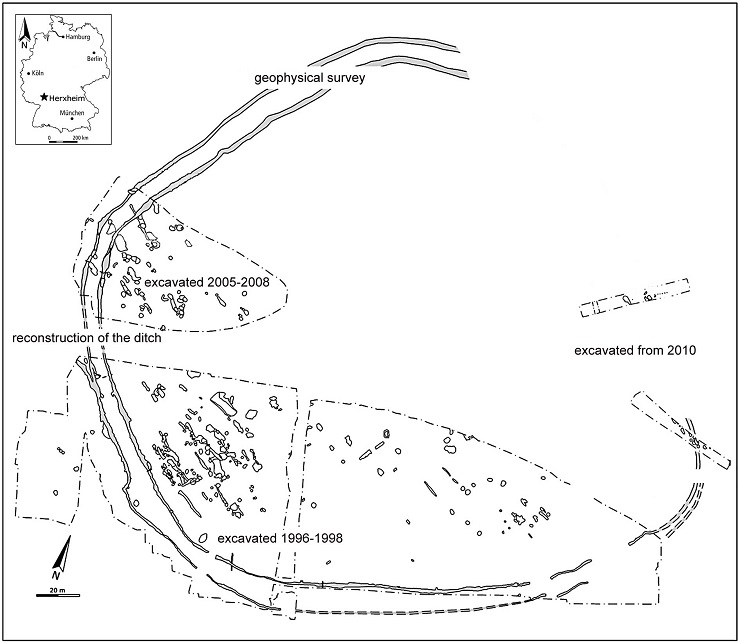

An unusually large number of buried human corpses showing signs of special treatment - this is what the Herxheim site located on the left bank of the Rhine in the southern part of the Rhineland-Palatinate provides us with. Archaeological surveying of this site has been carried out since the mid-1990’s. The oval pits on the site either overlapped or they were adjacent to each other and were arranged to generate a groundplan in the form of an irregular double ring around the settlement of the Linear Pottery culture. Two concentric lines thereby resembled trenches that were familiar from the chronologically later roundels.

The gradually excavation of the structures shows that this was not a one-off project, whether with any motive, but repeated as chronologically separate actions. In the infill of these objects a considerable number of human skeletons were found - some 500 skeletons that were deformed and/or broken in various different ways. “Standard” burials in a crouching position occurred only minimally. Since research was implemented on only about half of the area, it is believed that there may be up to 1000 individuals buried there. Such a large number of bodies could hardly have come from the surrounding settlements, small both in their scale and in their duration. Likewise, the time for which this burial (?) site was used was very short too - it is believed to have been a maximum length of 50 years, as is evidenced by the pottery items that were found. On the other hand, this chronologically similar pottery can be distinguished stylistically to the eight geographical areas from which it originates, that were as far apart from each other as 400-500 km. The technology utilised suggests that these were high quality goods, which also highlights the significance of this place. Another important finding is the discovery of the systematic and deliberate destruction of and/or damage to the pottery even before it was deposited in the location where it was subsequently found by the archaeologists. In addition to the broken pots also apparent there were some smaller relatively undamaged containers, the handles of which had been broken off, however. Also subjected to intentional damage were certain other artefacts including grinders and other stone tools and additionally anthropomorphic sculptures.

Let’s get back to the human remains. The presence of predominantly incomplete skeletons point to the fact that these were probably secondary burials, whereby the body or a portion thereof was transported from another location. The bones also bear traces of sawing, scraping or having been hit. If such marks were found on animal bones it would be considered as a proof of butchery. In the case of human skeletons therefore we think about cannibalism. These signs clearly indicate the separation of the soft tissues, scalping, the removal of the brain, the separation of the tongue, chipping the ribs, etc.

The strontium analysis is also significant in regard to its interpretation, which shows the non-local origin of the buried individuals and this corresponds with the findings in regard to the pottery. Nevertheless, the strontium analysis indicates that these people were supposed to grow up in mountainous areas, while the “standard” burials were probably of people of local origin.

The complex in Herxheim is considered as being a necropolis of another type, one that is associated with ritual practices and perhaps also with a religious background. Groups of incomers from the wider surrounding region brought with them the bodies of their dead, which were then handled as part of a special ceremony. Fire can have an important role in regard to ritual behaviour. What can be considered safely is the deliberate destruction of various types of artefacts and handling human remains, perhaps associated with cannibalism.

|

|

| The overall plan of the trenched area that was explored in Herxheim together with the remains of the settlement inside it (© GDKE, Direktion Landesarchäologie – Speyer). |

Want to learn more?

- Boulestin, B., A. Zeeb-Lanz, Ch. Jeunesse, F. Haack, R.-M. Arbogast, and A. Denaire. 2009. Mass cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture at Herxheim (Palatinate, Germany). Antiquity 83 (322): 968–982.

- Häusser, A. (ed.) 1998. Krieg oder Frieden? Herxheim vor 7 000 Jahren Herxheim: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege.

- Orschiedt, J., and M. N. Haidle. 2007. The LBK enclosure at Herxheim: Theatre of war or ritual centre? References from osteoarchaeological investigations. Journal of conflict archaeology 2: 152–167.

- Schmidt, K. 2004. Das bandkeramische Erdwerk von Herxheim bei Landau, Kreis Südliche Weinstrasse. Untersuchung der Erdwerksgräben. Germania 82: 333–349.

- Turck, R., B. Kober, J. Kontny, F. Haack, and A. Zeeb-Lanz. 2012. „Widely travelled people“ at Herxheim? Sr isotopes as indicators of mobility. In Population dynamics in prehistory and early history. New approaches using stable isotopes and genetics, eds. E. Kaiser, J. Burger, and W. Schier, 149–164. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Wild, E. M., P. Stadler, A. Häusser, W. Kutschera, P. Steier, M. Teschler-Nicola, J. Wahl, and H. J. Windl. 2004. Neolithic massacres: local skirmishes or general warfare in Europe? Radiocarbon 36 (1): 377–385.

- Zeeb-Lanz, A. 2009. Gewaltszenarien oder Sinnkrise? Die Grubenanlage von Herxheim und das Ende der Bandkeramik. In Krisen – Kulturwandel – Kontinuitäten. Zum Ende der Bandkeramik in Mitteleuropa. Beiträge der internationalen Tagung in Herxheim bei Landau (Pfalz) vom 14.–17. 6. 2007, ed. A. Zeeb-Lanz, 87–101. Rahden: Leidorf.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.png)