|

| The origins of the production of effective cutting tools, a gain of the Neolithic society, are also based on knowledge of ancient stone chipping. |

Although the documentation from the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods in regard to grinding stone and to manufacturing axes is now safely known, the use of this technology in Central Europe for the purpose of producing polished tools did not culminate until the Neolithic. The initial puzzlement concerning the function of some of the artefacts in a living culture has dissipated over time. Thanks to traceology and experiments undertaken with replicas of stone axes, today without any doubt they are interpreted as representing timber equipment. The initial hypothesis regarding the use of large drilled hammers as ploughs and the smaller adzes as hoes does not match the traces of use on the tools nor the contemporary ideas concerning the Neolithic agricultural production. However, their partial use for some fieldwork (breaking up clods and turf) cannot be excluded. Problematical, however, is to find and to be able to interpret the evidence of such activities. As is shown by ethnographic observation, the relationship between the form and the function of a tool in a living culture is never completely clear nor is it unchanging. Many tools that have the function of an adze were also used as axes and vice versa. Thanks to a strict functional link the morphology of these tools is not subject to any specific chronology to the same extent that the pottery or, more precisely, its decor is. Nevertheless at somewhat longer time intervals the polished stone industry also underwent its own chronological development.

Generally utilised for the production of polished artefacts in settlements were the blanks that had been brought from quarrying areas. This corresponds to certain findings discovered in those quarrying areas, where it is possible to encounter only blanks and seldom the finished products. On the other hand in any larger or more thoroughly explored settlement should be possible to find a greater or lesser quantity of evidence concerning the processing of blanks to produce finished products or the reutilisation of older damaged tools; there are boards showing traces of cutting, flakes of raw materials and fragments of broken tools and cores. The final shapes were formed from pieces of the raw material by using sandstone grinders.

The effectiveness-level of the stone axes is surprisingly high. It was found experimentally, using replicas, that for felling an oak with a diameter of 35 cm two lumberjacks need only fifty minutes. Other experimenters have also reported similar results. A dugout canoe was also successfully reconstructed using only stone tools.

|

|

| The resultant tool (on the right) has been formed by the successive grinding of an excised blank. |

|

|

| Even today jade axes are stunning based on the perfection of their workmanship. The findings from the Mazéres site in southern France. © Pierre Pétrequin, Université de Franche-Comté. |

|

|

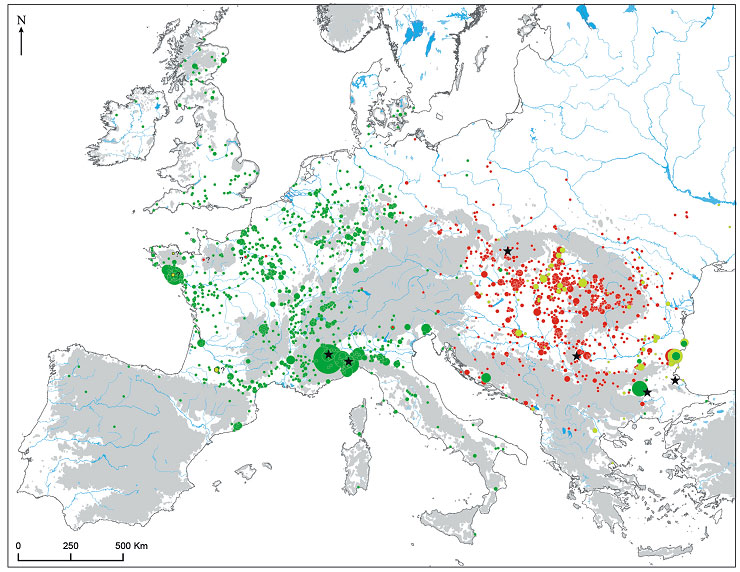

| The area of in which jade axes were utilised is seriously excluding the concurrent distribution of early copper. The point size corresponds to the degree of concentration of the findings. The axes from Alpine jade are marked in green; red = copper axes, yellow = gold discovery. The stars indicate the source locations of these raw materials. According to Domínguez-Bella et al. 2015. |

Want to learn more?

- Drnovský, V. 2011. Příspěvek k problematice dílen a výrobního řetězce broušené industrie. Živá archeologie – (Re)konstrukce a experiment v archeologii 12: 13–18.

- Oliva, M. 1985. Úvahy o pracovních a sociálních aspektech pravěké broušené industrie. Časopis Moravského muzea 70: 17–36.

- Pétrequin, P., and A. M. et al Pétrequin. 1998. From the Raw Material to the Neolithic Stone Axe. Production Processes and Social Context. In Understanding the Neolithic of North-Western Europe, eds. M. Edmonds, and C. Richards, 277-311. Glasgow: Cruithne Press.

- Whittle, A. 1995. Gifts from the earth: symbolic dimensions of the use and production of Neolithic flint and stone axes. Archaeologia Polona 33: 247-259.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.png)