It is natural for us to visualise ourselves as being a benchmark for the world that surrounds us. We define our opinion of ourselves by categorising ourselves in accordance with our surroundings. We essentially categorise objects, nature and people and we do so both constantly and unconsciously. This automatic form of social categorisation gives us the impression that anyone who is similar to us in regard to their clothing, their hairstyle or their manner of speech inspires a higher degree of confidence than someone who clearly represents a different category. We do not only categorise individuals but also groups and entire populations by means of a similar procedure. Tolerance of the range of similarity increases in accordance with the diversity of the social environment in which we are currently involved.

|

|

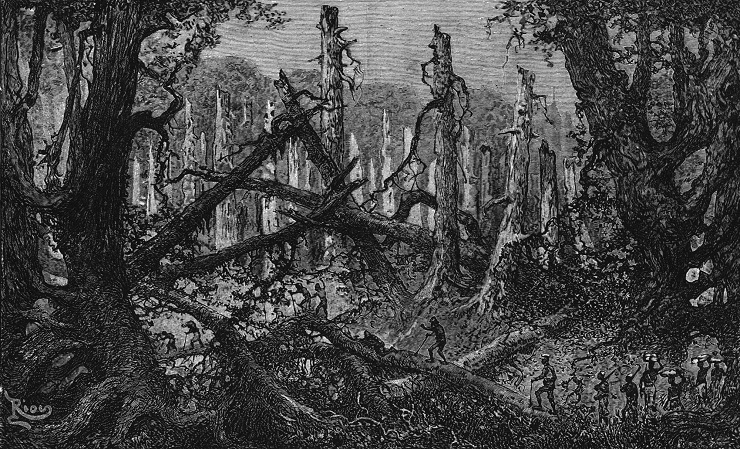

| During the 19th Century it was the romanticised African explorers who became a new type of hero. Their journeys, however, were not guided simple by their thirst for knowledge, but also by their awareness that the more new space that is discovered, the more there will also be that it will be possible to control. To take into account the fact that the so-called discovered regions had already been inhabited by local people was beyond the power of resolution of the way of thinking at that time. It was also in this spirit that the expedition proceeded, during the course of which Henry Morton Stanley crossed Africa from east to west. He is the man in the lower right corner of the image who has a hat on his head and a stick in his hand and is walking across a fallen trunk in the Ituri forest. (Stanley, 1891, 259). |

We approach those individuals who are really different with mistrust, especially when we take into account archaic societies with a pre-industrial economy – more frequently simply referred to as savages or primitive natives. All these definitions point towards difference as representing a negative factor. In the Western world, views of this nature do indeed have along tradition.

|

|

|

The tale entitled “The Last of the Mohicans” was the first of a series of Indian novels that have stimulated the imagination of an infinite number of both European and North American youngsters. Photo by Jan Bareš, 2014. |

The history of dividing “our world” from “the world of the others” commenced during overseas expeditions during which the actual discovery of diverse populations was a somewhat secondary facet of these voyages. It was not until the second half of the 18th Century during which, in the intellectual environment of the West, humanistic ideals associated with the philosophical concept began to emerge that every individual human being, group or nation should be seen as fundamentally good. It was this perspective that gave rise to the concept of the noble savage (bon sauvage). In essence, this represented idealising the pre-industrial culture as opposed to Western Society.

One representative example might be the approach adopted by Benjamin Franklin, who sought-out a path leading to a humanistic understanding of the differences between the white population and the Indians. “If an Indian injures me, does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians? It is well known that Indians are of different Tribes, Nations and Languages, as well as the White People. In Europe, if the French, who are White People, should injure the Dutch, are they to revenge it on the English, because they too are White People?” (B. Franklin, 1764).

However, The myth of the noble savage generally only found its response within the narrow circle of the intellectual elite, however. Not only ordinary residents of the western world, but also those who stood at the helm of power, still did not perceive “these others” very favourably. Their xenophobia was also influenced by Christian ideology. In addition the economic and the political interests of the Western empires were in conflict with the change of attitude towards the original inhabitants of the conquered and colonised territories. This was contrary, however, to the utopian concept of the noble savage that existed in the literary sphere - especially amongst the authors of Indian tales of adventure. Worth mentioning are the novel Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper, the character of Winnetou created by Karl May or Fritz Steuben’s stories featuring Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa.

|

|

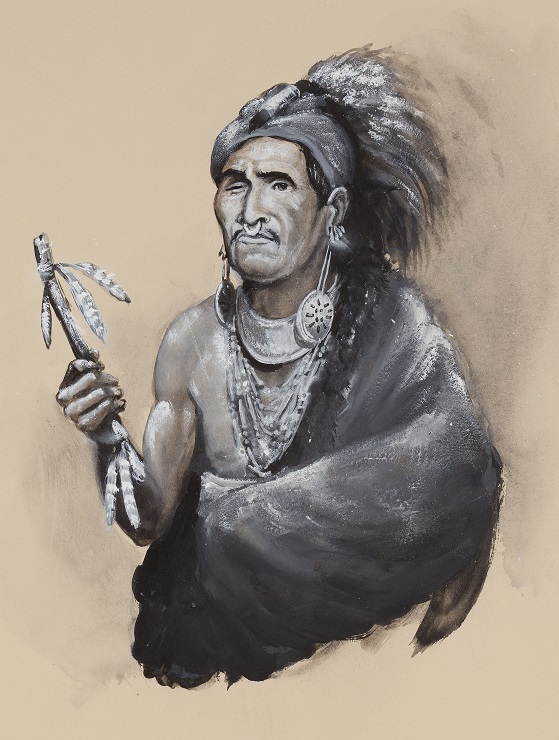

| Tenskwatawa (meaning Open Doors) Prophet was probably not a true spiritual leader, but rather an opportunist who took advantage of the tribe’s current needs for a moral resurgence. This need was directly related to the growing threat to the original Native American habitat, including it’s traditional value system. Tenskwatawa was probably charismatic and in any case very eloquent, as evidenced by his original name Lalawethika (meaning Chatterbox). Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

Want to learn more?

- Ellingson, T. J. 2001. The Myth of the Noble Savage. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Haible, B. 1998. Indianer im Dienste der NS-Ideologie. Untersuchungen zur Funktion von Jugendbüchern über nordamerikanische Indianer im Nationalsozialismus. Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovac.

- Kramer, T. 2005. Tecumseh und Toka-itho. Edle Wilde unter roten Brüdern. Zur Rezeption der Indianerbücher von Fritz Steuben und Liselotte Welskopf-Henrich in der DDR. Ethnographische Momentaufnahmen vol. 25. Berliner Blätter. Ethnographische und ethnologische Beiträge. Berlin: Gesellschaft für Ethnographie and Institut für Europäische Ethnologie.

- Wolf, E. R. 1982. Europe and the people without history. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)