For a long time the culture of the hunter-gatherer societies constituted the only economic manner of adaptation on the Earth. It is estimated that until 1500 one third of the entire world was inhabited by hunter-gatherers.

|

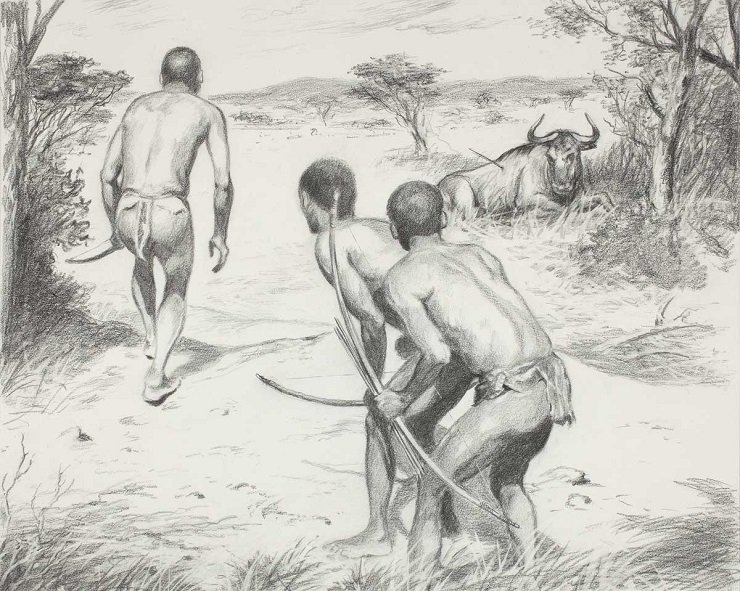

| Men of the hunter-gatherer !Kung population traced wild gnu wounded by a poisoned arrow in the red dunes of the Kalahari Desert. Compared to the general concept of hunting tracking such a large animal usually takes a few days and the failure of hunting expeditions is not at all unusual. Precisely for this reason, gathering organised by the females in the group is much more important in regard to everyday nutrition. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

The hunting-gathering culture is defined by its orientation to subsisting by hunting wild animals, by fishing and by gathering wild plants. No domesticated crops were grown and, of the domestic animals, it was only dogs that constituted part of the household. To the present day only remnants of these societies have been preserved; specifically those that inhabited environmentally marginal areas, which often also indicated their more or less involuntary adaptation to a specific habitat zone. These societies, however, cannot be considered as constituting living witnesses of prehistory; there is only an apparent similarity. Indigenous Australians have probably never known any other way of living than a predatory one, whereas, in the past, the Kalahari Bushmen, for example, had even encountered certain elements of domestication. In the Amazon rainforest area we know of cases in which evolutionary adaptation alternated from hunter-gatherer to agricultural sustenance and back again.

Also important are the geographical and the cultural contexts - whether or not hunters were also found in the area, and/or if they maintained relationships with their agricultural neighbours. In this situation, the hunters became partly dependent on others (e.g. through connections made between hunter-gatherers in South and Southeast Asia and settled agricultural populations and their mutual trading, or between Pygmies and sedentary farmers in Central Africa). South American natives who, after the era of the conquistadors (the 16th -17th Century), re-adapted from tropical agriculture to hunting and gathering or used a combination of both means of subsistence represent a separate category.

|

|

| Economic relations between black farmers and the Pygmy hunter-gatherers were based on the subordinate relationship of the latter to the former. “I’m just a poor BaMbuti. The forest is my father and my mother. When my black master tells me to bring meat, I go out to hunt...,” the Pygmy hunter Cephu said about himself. The illustration by Petr Modlitba is based on a photographic artwork from 1959 by Pavel Jáchym Šebesta. |

The neighbouring world did not register the existence of the indigenous population of Amahuaca who inhabited southeastern Amazon in Peru and Brazil, until the 18th Century. A small settlement consisting of 15-20 persons was considered to be a basic residential unit. The community was both economically and politically self-sufficient and it recognised the moral authority of the eldest male. Settlements moved often with a frequency of roughly one-year. The impetus for leaving the former location was the concern for there being a sufficient number of animals within the area of the accessible hunting territory. Gardens were established on the tops of the hills and their fertility also represented a reason for making a move. The basic crop grown was corn accompanied by a wide range of other crops. Because of the tense atmosphere due to frequent wars amongst the natives, frequent changes of cultivated land and of places in which to live constituted part of a defensive strategy.

Communities of hunter-gatherers that amounted to 15-50 people exhibited a strong tendency toward egalitarianism. Even there private property still existed while asset sharing was subject to the rules of reciprocity. Within the group great men or leaders of activities could have a greater influence while those who disagreed with them were free to leave the group. Overall the territory was usually jointly owned by groups that were also linked by family ties.

Hunter-gatherer groups might differ in their approach to warfare - some of them were described by ethnographers as being peaceful while for others war constituted a ubiquitous part of their lives. Also the position of women differed; in many cases it was higher and more equal with men than it was in the archaic agricultural or even the modern industrial societies. On the other hand, in certain groups of Inuit Eskimos or of Aborigines in northern Australia the social position of women was very low and did not rule out violence against them with impunity. The widest differences within the predatory companies arise, however, from the comparison between simple and complex hunter-gatherers. In certain environmentally specific areas much larger and more complex social formations of hunter-gatherers have been created. Their economic background that has included food storage and long-distance trading, together with their political power apparatus is comparable to that of similar populations of farmers. Also typical of this category was the number of indigenous populations of the Northwest Coast of North America or of Chumash Indians from Central and Southern California. Though they depended solely on non-domestic sources, their social classes included nobles, plebeians and slaves. In regard to trade the Chumash Indians used pre-monetary tender while also creating extensive residential centres.

|

| The landscape of the North American plains with its grazing herds of bison was home to the local hunter-gatherer population. They even dared to hunt the ancestors of today’s bison that reached a height of 2.3 metres and weighed more than 1500 kg. On contrary to traditional ideas, represented in the picture, hunting one of these giants could not be carried out from the saddle, since riding horses had not yet been brought to America by Europeans. Bison hunting was therefore traditionally carried-out by pedestrian hunters who took advantage of their perfect knowledge of the landscape. Illustration by Petr Modlitba. |

|

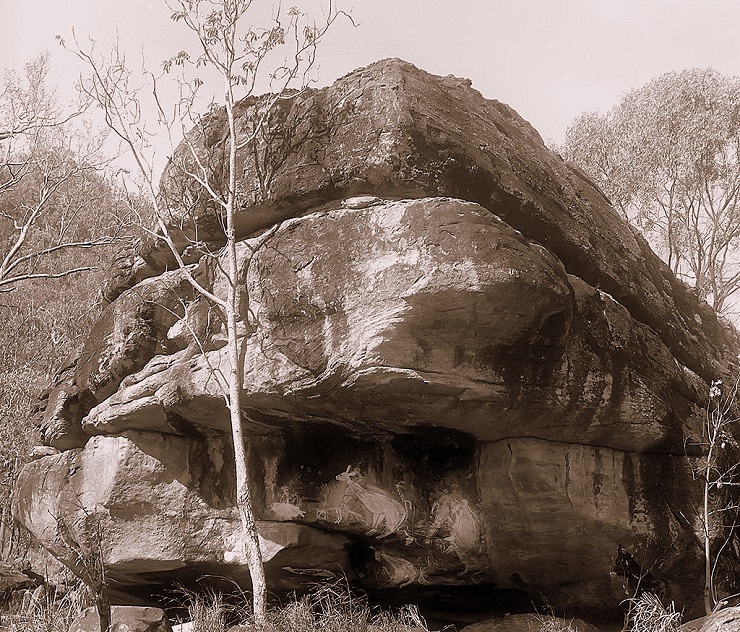

| The rock in the Goomadir River lies on the “Song Road” of the Aborigines from Arnhem Land. Their connection to the spiritual beings of the ancient dreaming period is confirmed by their paintings under the eave. Photos from the Moravian Land Museum’s Australian expedition in 1969. |

Want to learn more?

- Barnard, A. 2004. Hunting-and-gathering society: an eighteenth-century Scottish invention. In Hunter-Gatherers in History, Archaeology and Anthropology, ed. A. Barnard, 31-43. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Bellwood, P. 2002. Archaeology of Southeast Asian hunters and gatherers. In The Cambridge encyclopaedia of hunters and gatherers, eds. R. B. Lee, and R. Daly, 284-288. Cambridge, U.K. and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Carneiro, R. 1964. Shifting cultivation among the Amahuaca of eastern Peru. Völkerkundliche Abhandlungen (Hanover) 1:9-18.

- Drucker, P. 1955. Indians of the Northwest Coast. New York: The Natural History Press.

- Gamble, L. H. 2008. The Chumash world at European contact: power, trade, and feasting among complex hunter-gatherers. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lee, R. B., and I. DeVore. 1968. Man the hunter. Chicago: Aldine.

- Peterson, J. T. 1978. Hunter - Gatherer/Farmer Exchange. American Anthropologist 80/2:335-351.

- Roosevelt, A. 2002. Archaeology of South American hunters and gatherers. In The Cambridge encyclopaedia of hunters and gatherers, eds. R. B. Lee, and R. Daly, 86-91. Cambridge, U.K. and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Turnbull, C. M. 1961. The Forest People. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Turnbull, C. M. 1965. Wayward servants: the two worlds of the African pygmies. [1st ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Natural History Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)