The African continent and specifically the NE part of it can be described as representing a laboratory, in which it is possible to test the different hypotheses that have appeared in regard to neolithisation that are based on research into and knowledge of the Near East and of Europe. These days most researchers accept the fact that the Neolithic package of changes, as we know it in these parts of the world, were accepted there in a different ratio and also in a different sequence.

|

| The globularly shaped pottery vessels decorated with wavy lines are among the oldest of their kind in Africa, and they had preceded the other items comprising the Neolithic package by several centuries. This fragment belongs to the Incised Wavy Line tradition that exists in Khartoum province. Research by the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký, 2012. |

For example, inhabited settlements with plenty of vital raw materials and other resources had already existed year-round in central Sudan 9000 years ago (the local Mesolithic). Finds of pottery dating back to middle of the 7th millennium BC (and according to some researchers even earlier) are also surprisingly common. The production of pottery vessels represents an innovation that had already been initiated in NE Africa many centuries earlier, quite independently of the domestication of plants and animals, which are considered as being typical features of the Neolithic. The Mesolithic regions appear not to have been completely isolated. Conversely, it is also possible to assume that there were large movements of people, goods and also ideas over vast areas. The combination of the manner of decorating the ceramic vessels together with the utilisation of similar production techniques provides an excellent source of information.

At the cusp of the 6th and 5th millennium BC changes to the material culture had taken place. One possible cause of this could have been climate change. Until that point-in-time, the Sahara region had been a rich reservoir of both plant and animal resources and the location of many watercourses and lakes. The level of the Nile River was several metres higher than it is at present. Around the 4th millennium BC, however, there had been great changes in the Sahara lake system and extensive drying out had begun. This resulted in changes to the local biomass and important resources. The Nile Delta Region, located in the northern part of NE Africa, functioned as a long-term transit zone along the Mediterranean coastline while the Sinai link served the Middle East. This can be demonstrated both by the artefacts that have been found at certain Egyptian sites, and also by the occurrence of Near Eastern species of domesticated animals and plants (i.e. barley and wheat).

|

|

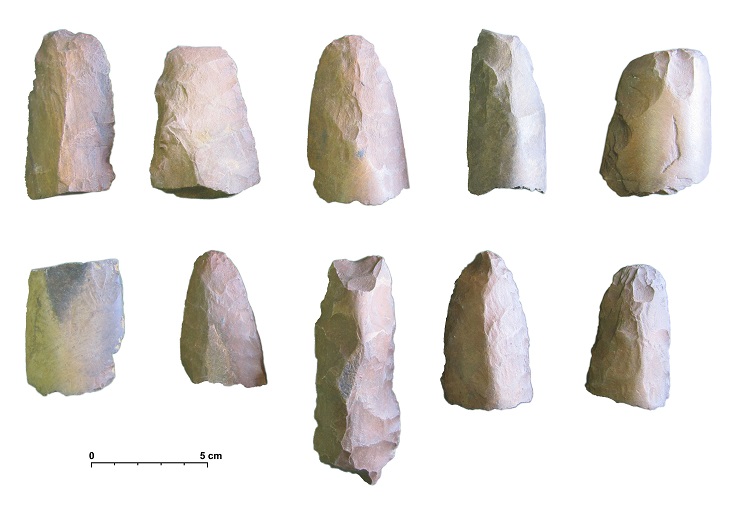

| Tools made by grinding characterise the Sudanese Neolithic. The Gouges come from the Fox Hill site located north of Khartoum. Research by the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký 2013. |

|

| By-and-large, simple shelters constructed from organic materials are archaeologically elusive. Due to the erosion of the surface layers that has taken place no pits are documented for anchoring the posthole structures. Similar structures could also be used (but not exclusively) in the African Mesolithic and Neolithic. Central Sudan. Research by the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký 2012. |

In accordance with experts on Africa, however, adopting the Neolithic way of life was not necessarily dependent only on natural pressure. At the end of the 6th millennium BC there were still sufficient resources in NE Africa that could be used for subsistence, so in principle no existential change determined by nature was required. There might be a number of other possible causes, however. It is likely that even in this geographic area what first took place were changes in the social and the value systems of the society. The burial sites (including children’s funerals with equipment) are indicators of population growth – the graves now also contain personal ornaments, tools and weapons. In the settlements storage pits are also documented – providing the first evidence of the accumulation of stocks and of property.

During the time of population growth and of the expansion of the traditional oecumene it is considered that in the area of NE Africa these factors led to the creation of social tensions during the Late Mesolithic period and later on within the Neolithic communities too. Due to the accumulation of stocks and of property and the defining of the territories for grazing and thereby the likelihood of this also leading to ownership conflicts, evidently it is certainly possible to envisage changes in the societal hierarchy taking–place together with some new forms of defining both individual and group identities. Also the domesticated animals represented an important new element of the economic, the social and also the ritual perspective. Given the relatively regular occurrence of the importing of raw materials the distribution network had stabilised; aspect of control of raw material outcrops could then become prestigious, however, or even a control over the distribution of raw materials and of derived artefacts. Communities located at greater distances from the sources of raw materials could become somewhat dependent on groups that practiced the barter system.

We can summarise that acceptance of the Neolithic way of life that was oriented largely towards animal husbandry was driven not only by natural factors, but first and foremost it may represent the result of a long-term process of social change. The Neolithic way of life had originally spread in Africa, and, as in Europe, it had spread there - from Western Sahara and along the Nile - using the same communications networks.

|

|

| Lightweight pens for animals also constituted an integral part of the Neolithic settlements. Virtually no archaeological traces of them are detectable however. Central Sudan. Research by the Czech Institute of Egyptology in Prague. Photo by Jaroslav Řídký 2012. |

Want to learn more?

- Arkell, A. J. 1953: Shaheinab. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dittrich, A. 2011: Zur Neolithisierung des Mittleren Niltals und angrenzender Regionen. Kultureller Wandel vom Mesolithikum zum Neolithikum im Nord- und Zentralsudan. BAR International Series 2281. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Fernández, V. M. (ed.) 2003: The Blue Nile Project – Holocene Archaeology in Central Sudan. Complutum. Madrid: Departamento de Prehistoria de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Haaland, R. – Haaland, G. 2013: Early Farming Societies along the Nile. In: P. Mitchell – P. Lane: The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 541-553.

- Hendrickx, S. – Huyge, D. 2014: Neolithic and Predynastic Egypt. In: C. Renfrew – P. Bahn: The Cambridge World Prehistory. Volume 1: Africa, South and Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Cambridge University Press, 240-258.

- Krzyźaniak, L. 2011: Changes in the natural environment between 8000 and 3000 BC. In: M. Chłodnicki – M. Kobusiewicz – K. Kroeper (eds.): The Lech Krzyźaniak excavations in the Sudan. Studies in African Archaeology. Poznań: Poznań Archaeological Museum.

- Renfrew, C. – Bahn, P. eds. 2014: The Cambridge World Prehistory. Volume 1: Africa, South and Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Cambridge University Press.

- Suková, L. – Varadzin, L. – Pokorný, P. 2014: Prehistoric Research at Jebel Sabaloka, Central Sudan (2011-2014). In: The Dolní Věstonice Studies, Vol. 20 – Mikulov Anthropology Meeting 2014, 149-153.

- Wengrow, D. 2006: The Archaeology of Early Egypt. Social Transformations in North-East Africa, 10.000 to 5650 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

Archeologické 3D virtuální muzeum

.jpg)